Peripheral artery disease: An update

For the first time in decades, there's a new therapy for this often-unrecognized cause of leg pain.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

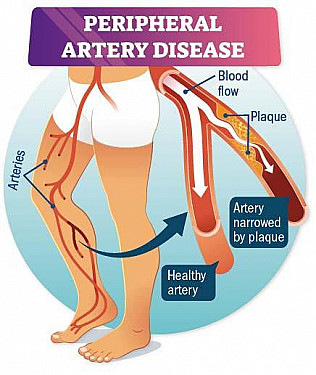

Fatty plaque can accumulate not only in the arteries that supply your heart, but also the ones in your legs. Known as peripheral artery disease (PAD), this plaque buildup can cause a painful, crampy sensation or even just fatigue in one or both legs when you walk. The discomfort is called claudication, from the Latin word meaning “to limp.”

Smoking, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol increase the risk of PAD, which affects nearly one in three people over age 75. Beyond quitting smoking, regular walking is the best treatment for PAD. Now, a new study shows that semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) can help people with PAD and diabetes walk farther and also improve their quality of life (see “An already approved drug finds use for PAD”).

“It’s the first new drug for function and symptoms in PAD in 25 years, after many attempts to find novel therapies,” says study leader Dr. Marc Bonaca, a lecturer in medicine at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Semaglutide’s positive effects for PAD appeared to be only weakly linked to weight loss. Instead, they are more likely related to improvements in vascular function, which suggests the drug has a direct effect on blood vessel health. These findings may help researchers better understand the drug’s broad health benefits, which probably involve anti-inflammatory properties, he adds.

PAD blockages and symptoms

Clogged arteries in the legs can limit blood flow during exercise, causing painful cramping — the hallmark symptom of peripheral artery disease. Image: © Nicole Wall/Getty Images |

An often-delayed diagnosis

Even though PAD is common, it often goes unrecognized. “The symptoms can be vague, and many people attribute achy legs to arthritis or simply growing older,” says Dr. Bonaca. Also, people may gradually change their behavior to walk less, such as parking closer to a store and avoiding stairs, he adds.

There are no routine screening guidelines for PAD — another reason the disease remains underdiagnosed. But earlier detection and treatment can stave off the serious consequences, which include sores on the toes, feet, or legs that won’t heal — or even leg amputation. If you suspect you may have PAD, ask your doctor about getting tested.

Detecting PAD

A simple test called the ankle-brachial index can detect PAD. Using a special cuff, the doctor measures the blood pressure in your ankles and compares it with the blood pressure reading in your arms, at rest and sometimes after a brief period of exercise. When your blood vessels are healthy, the readings should closely match. A big difference between the arm and the ankle signals that blood isn’t moving well through clogged vessels in your lower body.

An already approved drug finds use for PADMedications for PAD are similar to those for coronary artery disease, such as drugs to lower cholesterol and prevent blood clots. In 2000, the FDA approved cilostazol, which helps ease leg pain and improves walking distance in people with PAD. But the drug’s gastrointestinal side effects and other issues have limited its use. Because semaglutide (sold as Ozempic for diabetes and Wegovy for weight loss) has proven benefits for lowering cardiovascular risk, researchers tested the drug in people with PAD. The STRIDE trial included nearly 800 people with PAD and diabetes who were enrolled at 112 medical centers throughout North America, Asia, and Europe. Most of the participants were men, with an average age of 68, and all reported intermittent claudication that made walking a challenge. They were randomly assigned to receive weekly doses of semaglutide or a placebo for one year and did treadmill walking tests at the start, middle, and end of the study. Those taking semaglutide improved their walking distance by an average of approximately 131 feet; they also had significant improvements in pain-free walking distance and quality of life compared to those taking a placebo. The study was published May 3, 2025, in The Lancet. |

An exercise prescription

People with PAD may be hesitant to walk, believing their leg pain is harmful. In fact, the opposite is true — walking is the best way to slow the progression of PAD and reduce its complications. Walking encourages blood flow in the leg’s smaller arteries and also creates new channels that move blood around the blocked areas, which eventually helps ease the pain. Ideally, you should walk for at least 30 minutes at least three times a week. Make sure to walk continuously until you feel leg pain, rest until it subsides, and then continue.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.